Two mills and a camp with 22 buildings. The Livingston is one of the most intact mining operations I've seen in Idaho, and it has a caretaker who lives on-site.

On the way in, we spotted the word "Trump" painted on one of the buildings. When I asked the caretaker about it, he shrugged: "You never know. He might see it and like the place." Fair enough. He was happy to show us around.

History

A.S. and W.S. Livingston staked these claims on July 28, 1882. The isolation was the problem: the deposit sat at 10,000 feet at the head of Jim Creek on Railroad Ridge, with no road worthy of the name. Early ore went out on mule trains to the Clayton smelter, some shipped as far as Denver. The production records from those years are lost, but the smelter returns that survive show ore running 30 to 50 percent lead and sometimes over 100 ounces of silver per ton.

The property changed hands in 1922 when Livingston Mines Corporation took over. They spent heavily: $50,000 on a new road connecting the mine to the East Fork of the Salmon River, $45,000 on a three-mile aerial tramway, $35,000 on a 380-horsepower hydroelectric plant on Boulder Creek, and $50,000 on a 300-ton-per-day stamp mill. They purchased twelve three-ton Mack trucks to haul concentrates the 60 miles to the railroad at Mackay. The tramway headhouse where ore began its three-mile trip down to the mill still stands up on the mountain. The stamp mill itself, built on the steep hillside where gravity could move ore through each processing stage, has mostly collapsed. Only a few concrete pillars remain of the lower section, though the upper floors still stand.

The investment paid off. In late 1925, a crosscut on the 2,200-foot level hit a massive ore shoot that became known as the Christmas stope. The Inspector of Mines called it "the biggest discovery of lead-zinc-silver ore in southern Idaho during the past 30 years." By 1927, the Livingston had the largest payroll of any mine in southern Idaho, with nearly 100 men working underground and at the mill. In 1929, outside the Coeur d'Alene district, the mine ranked first in Idaho for lead production and second for silver.

Then came the crash. The mine closed in July 1930 and entered receivership that December. The property passed through several hands during the Depression, including Lewis Twynman of Miami in 1934 and G. Spencer Hinsdale's H. & H. Mines in 1938.

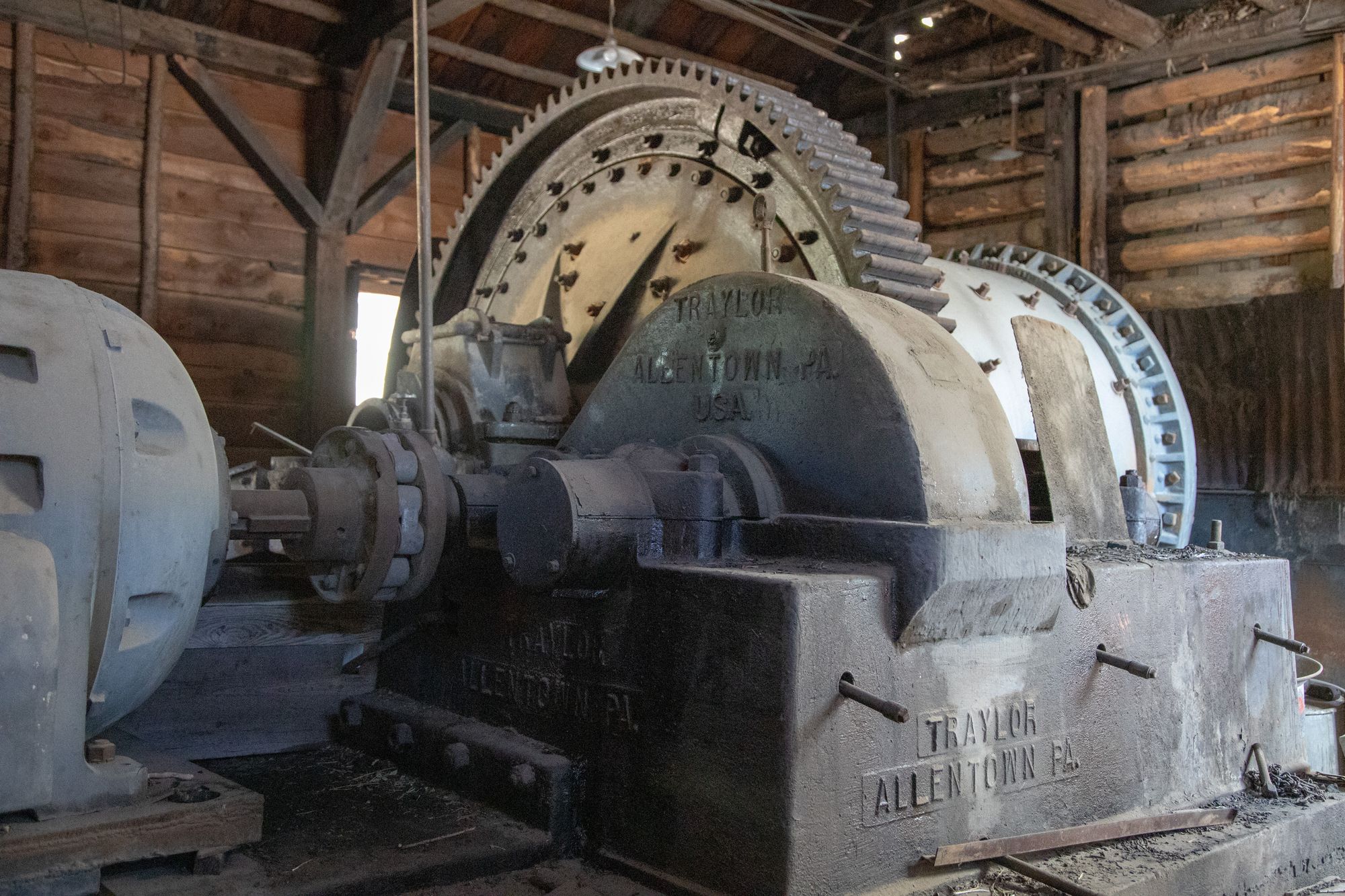

A new company, Livingston Mines, Inc., purchased the property in 1946. They bought a 100-ton flotation mill in 1948 and had it delivered to the property. This is the mill near camp, the one that's nearly intact. The postwar operation was smaller than the 1920s peak, shipping ore to custom mills in Utah rather than running everything through on site. Idaho Custer Mines acquired the property in 1951 and spent several years reprocessing the old tailings piles. The company also explored for deeper ore with help from a Defense Minerals Exploration Administration loan and, briefly, Hecla Mining Company. The exploration found some mineralization but nothing that justified reopening.

Over its lifetime, the Livingston produced 543,000 ounces of silver and 17 million pounds of lead from about 87,000 tons of ore. The main ore shoot, the Christmas stope, was mined through a pitch length of 1,550 feet, with widths up to 30 feet of solid sulfide ore.